Nouvelle Vague

Richard Linklater’s tribute to the cinema of the French New Wave defies the odds to emerge triumphant.

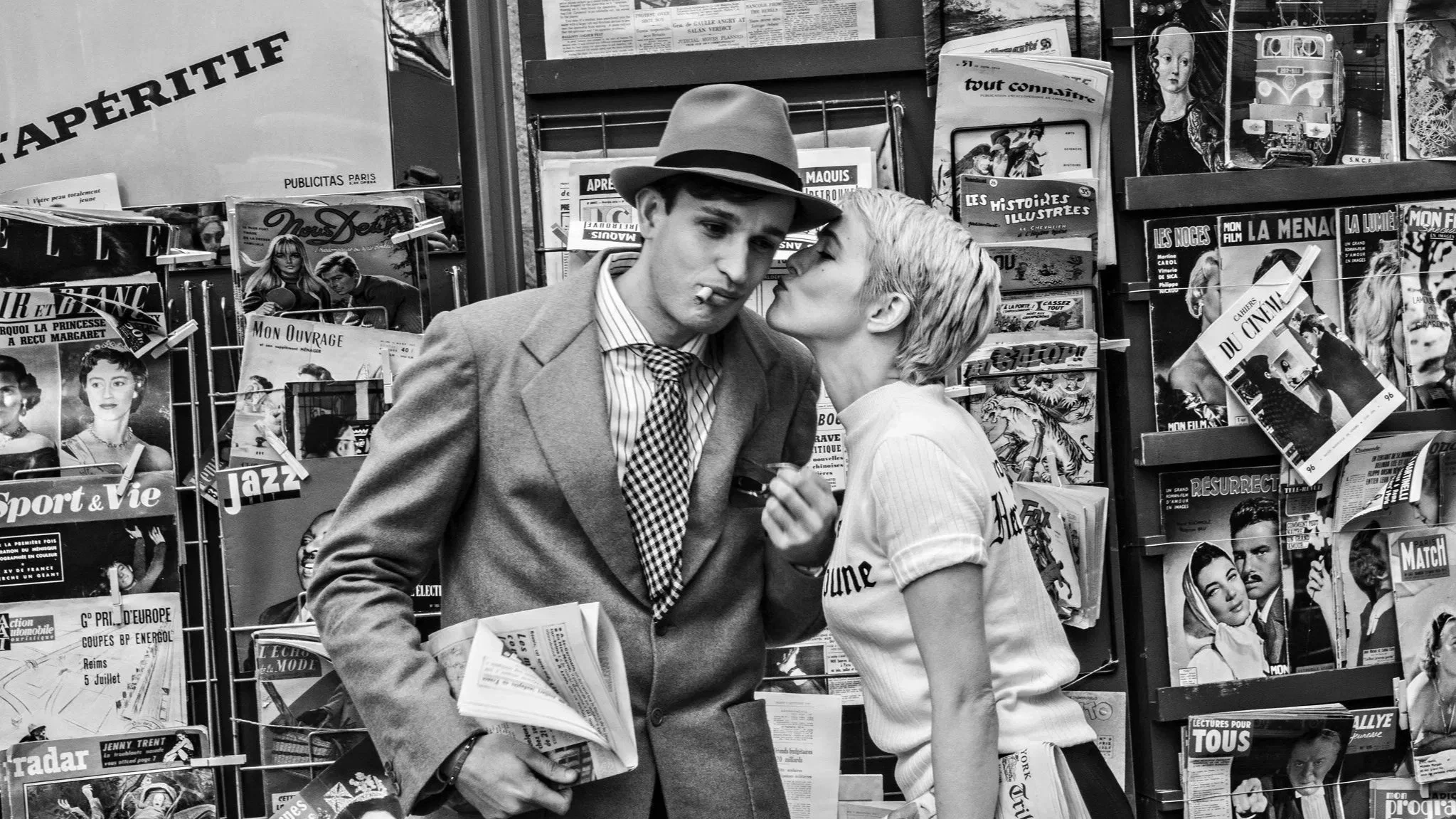

Aubry Dullin and Zoey Deutch

Image courtesy of Altitude Film Distribution.

by MANSEL STIMPSON

Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague is an extraordinary achievement especially when one considers how easily the project could have gone awry. The film was born of Linklater's wish to pay homage to those involved in what became known as the French New Wave, the movement that started in the late 1950s and introduced a wide range of new and talented filmmakers. They were consciously reacting against what they saw as the increasingly staid and lifeless work that had become so widespread in French cinema. Many in the group had already established themselves as critics writing for the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma but very quickly they would rise to the forefront of French directors and become internationally recognised. Amongst them were François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, Éric Rohmer and Jean-Luc Godard. The latter was not the first of them to make his mark. Chabrol had already directed Le beau Serge and Truffaut had triumphed at Cannes in 1959 with Les quatre cents coups before Godard created a huge if initially controversial impact with his debut feature À bout de souffle (more readily known these days under its English title Breathless)). Its release came in 1960.

It is the making of Godard’s first feature which is the subject of Linklater’s film and most audiences drawn to it will have seen Breathless at some stage. It was a film which would not only prove highly influential but which has gained a great reputation that has only grown with the passage of time (fittingly there was a cinema release for a restored version on its fiftieth anniversary). The fact that Godard's methods were so new and that he was virtually untried at the time of making it meant that the tale of its production involved a huge gamble on the part of the producer Georges de Beauregard. Indeed, there was real uncertainty as to whether or not the film would work and, when filming started, there was a sense of strong unease on the part of its leading actress Jean Seberg, the one established player involved. She had suffered from the experience of starting her film career with two movies directed by Otto Preminger whose treatment of her she regarded as sadistic, but she now felt that she had entered a madhouse. To help get the film set up it had been emphasised that it was based on a story by Truffaut and that Chabrol was also associated with it when in fact it would go ahead without a proper screenplay. It was to be shot in twenty days but, instead of being planned out in advance, there was a conscious reliance on the inspiration of the moment and on last minute improvisation and it began without any certainty as to which of two very different endings would be adopted. Furthermore, whenever Godard became uncertain as it proceeded, he was quite ready to cut short a day’s shooting regardless of the producer’s absolute consternation.

Nouvelle Vague sets the scene by showing how Breathless became a project and then takes us through the actual shooting of it on a day-by-day basis. Consequently, it is a film that will work on different levels depending on how familiar each viewer is with À bout de souffle. Linklater rightly opts to have his film shot in black-and-white to match the original and to capture nostalgically the Paris of 1959. Recreating the shooting of Breathless involves acting out numerous scenes or snippets as seen in the original and the hazard here is obvious in that Linklater’s cast have to persuade us to accept them as being the people who actually took part in it. The problem is patently at its most acute when it comes to actors pretending to be Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo but, while one is less familiar with how such figures as Truffaut and Chabrol looked at the time, even Godard himself counts as relatively known to us albeit behind those familiar dark glasses. Luckily - and to my mind amazingly – the casting of Nouvelle Vague which uses mainly relatively unfamiliar faces is one of the film's great successes. It is quite easy to accept Guillaume Marbeck as Godard and Aubry Dullin catches the essence of the young Jean-Paul Belmondo. Even more surprisingly given that Breathless contains an iconic performance by Jean Seberg, we find this film’s best-known name, Zoey Deutch, creating a Seberg in whom we really do believe (she falls short only when her street vendor’s cry of "New York Herald Tribune" can't match its delivery by Seberg herself!).

Admirers of Breathless will welcome this admirably written and persuasive account of its filming. The screenplay takes full but never forced advantage of Godard’s fondness for aphorisms about cinema and it captures admirably the contrasted reactions of Seberg and Belmondo to Godard’s wayward but inventive approach – she initially shocked by the absence of professionalism and he, a boxer who would only subsequently have a career as a major film star, relaxed about it all having previously appeared in a short film for Godard. Only occasionally does Linklater seek to emulate Godard directly (a road journey to Cannes seen early on echoes the opening images of Breathless and like Godard he makes use of jazz music on the soundtrack but intelligently opts for a jazz sound more in harmony with this film’s nostalgic evocation of the past).

While it is an advantage for those viewing Nouvelle Vague to have already seen Breathless, two factors make it appealing regardless of that. One is the way in which Linklater’s film captures the adventurous spirit of the young filmmakers and their associates embarking on a venture of daring originality. Godard comments on the fact that he spurns formal narrative because the instantaneous and the unexpected are excluded by it and À bout de souffle was an attempt to rectify that. The commitment to this is something younger viewers especially can identify with and thus feel involved even if they have yet to see Breathless. The other factor that shines through and makes Nouvelle Vague so appealing is that it is patently a labour of love by Linklater. Two details epitomise his care and concern. One is a short scene in which the director Robert Bresson is encountered shooting his film Pickpocket and we glimpse an actor in the background. It is that film’s lead actor Martin LaSalle and, although his presence is hardly noted, Linklater nevertheless takes the trouble to find someone who resembles LaSalle. The other lies in the way in which all those connected with Breathless are named when first appearing, including for example the lead editor and her assistant seen briefly near the close. Obviously many of these names will mean nothing to most of the viewers but Linklater wants to honour all of them. Their collective work fed into Breathless and Nouvelle Vague salutes all those who contribute in their own particular way to the remarkable adventure of making a film.

Cast: Guillaume Marbeck, Zoey Deutch, Aubry Dullin, Adrien Rouyard, Bruno Dreyfürst, Matthieu Peninchat, Jodie Ruth-Forest, Pauline Belle, Paolo Luka-Noé, Tom Novembre, Antoine Besson, Benjamin Clery, Jade Phan-Gia, Lea Luce Busato, Jonas Marmy, Laurent Mothe.

Dir Richard Linklater, Pro Michèle Pétin and Laurent Pétin, Screenplay Holly Gent and Vince Palmo, with Michele Halberstadt and Laetitia Masson, Ph David Chambille, Pro Des Katia Wyszkop, Ed Catherine Schwartz, Costumes Pascaline Chavanne.

ARP Sélection/Detour Filmproduction/Ciné+OS/CNC/Canal+-Altitude Film Distribution.

106 mins. France/USA. 2025. US Rel: 31 October 2025. UK Rel: 30 January 2026. Cert. 12A.