Hearts of Darkness: Writer/Director Fax Bahr Reflects on the Legacy of Coppola’s ‘Apocalypse Now’

All images courtesy of Rialto Pictures / American Zoetrope

by CHAD KENNERK

Named after Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, on which Apocalypse Now is loosely based, the 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse chronicles the notoriously chaotic production behind director Francis Ford Coppola’s ambitious Vietnam War epic. With the monumental success of The Godfather films, hopes were high for Apocalypse Now, which was poised to be the acclaimed director’s magnum opus. Shot on location in the unforgiving jungles of the Philippines, Apocalypse was plagued with typhoons, ravaged sets, delays and emotional breakdowns, all of which seemed to mirror the madness of the on-screen voyage.

Set during the Vietnam War, Apocalypse Now is a surreal exploration of the moral and psychological disintegration caused by violence and imperialism. It follows Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) on a mission to assassinate Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), a rogue military officer who had reportedly gone mad and set himself up as a god among the indigenous people of Cambodia. From the moment production began in 1976, it was beset by unforeseen challenges. In the midst of this, Eleanor Coppola — director Francis Ford Coppola’s wife — began shooting 16mm footage to document the making of the movie for United Artists’ publicity department. What eventually emerged was both a history of the ‘making of’ process and a commentary on filmmaking itself, offering a raw look at the tumultuous journey to complete the 1979 masterwork, which went on to win Academy Awards, the Palme d'Or, and further solidified Coppola's reputation as one of the great directors of his generation.

Written and directed by Fax Bahr with George Hickenlooper, Hearts of Darkness depicts the challenges Coppola and crew faced, painting a portrait of ambition, ego and self-doubt as Coppola risked everything to make a cinematic statement. Producers George Zaloom and Les Mayfield initially approached Coppola’s production company, American Zoetrope, and producer Fred Roos in 1989 about Eleanor’s legendary footage. With director and co-writer Bahr, they developed a proposal to look back on the making of Apocalypse Now. The result was an intimate and often harrowing exploration of an artist in the throes of realising a creative vision, offering audiences the opportunity to witness the ferocious spirit of artistry that nearly wrecked its creator. As the 1991 documentary reveals, Coppola’s journey was not only about making a movie — it was about confronting his own limitations and hubris in the post-studio era of the auteur filmmaker.

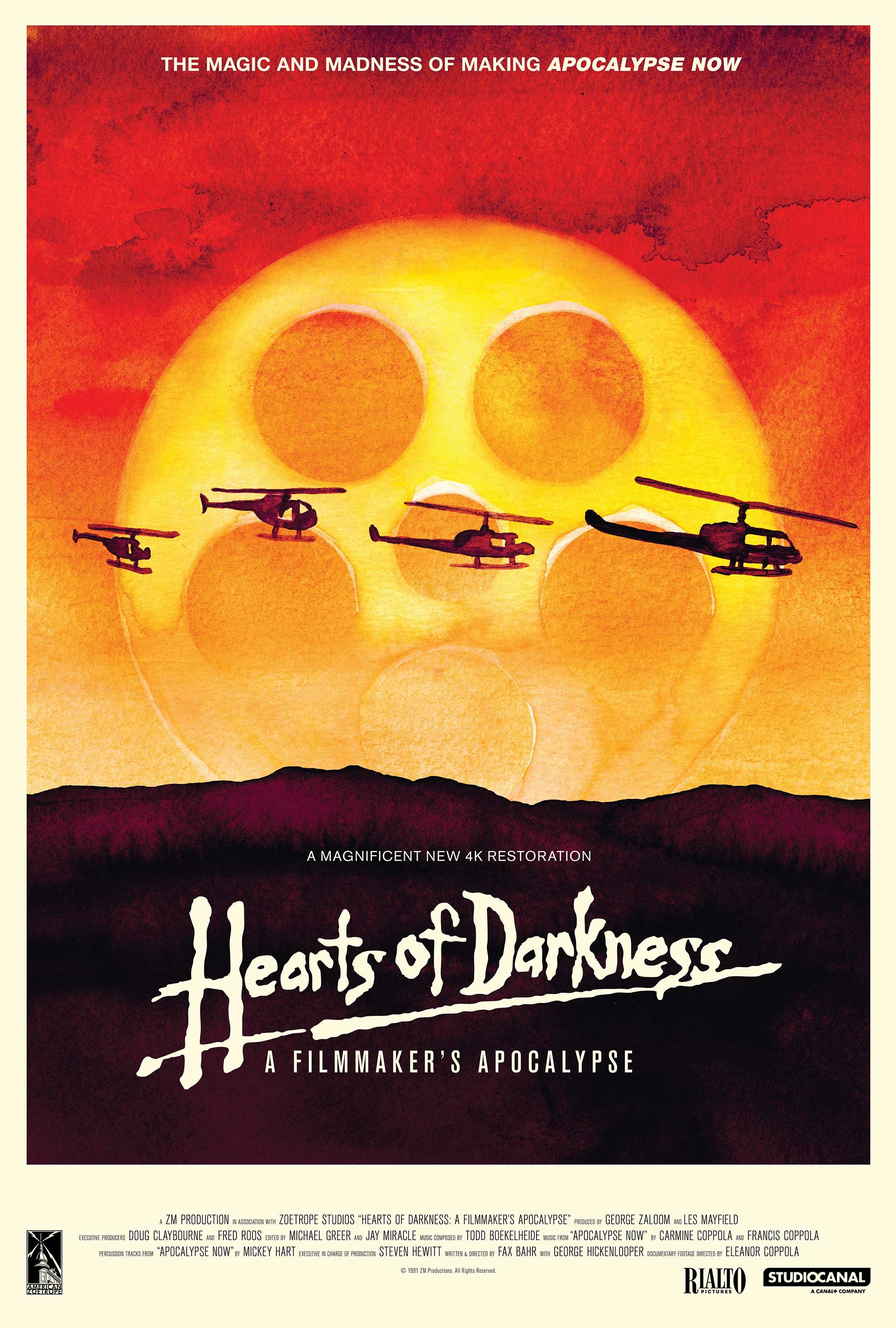

Now, over three decades after its original release, Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse returns to the big screen in a 4K restoration from American Zoetrope and Rialto Pictures. For the restoration, archivist James Mockoski returned to the original sources, scanning elements in 4K and remastering the soundtrack to create a new 5.1 mix. The restored film is currently being screened in select theatres, offering a unique lens on Apocalypse Now, as well as the passion, madness, and genius that defined the American cinema of the 70s.

In conversation with Writer/Director Fax Bahr.

Film Review (FR): You came into this project as an observer through Eleanor Coppola's unique perspective as an observer. What was that moment like — receiving a treasure trove of materials?

Fax Bahr (FB): It was the thrill of a lifetime, really. We had seen some of the [footage], and it looked really good, but when all the footage came down, [it was] reel after reel of her meticulous documenting of this monumental production. It was just one gem after another.

(FR): There were several attempts at a documentary during the production of Apocalypse Now, but the footage was eventually placed in storage and essentially forgotten. What was your process to find a solution to the puzzle? What led to your initial outline?

(FB): Prior to Apocalypse, I was a huge fan of Heart of Darkness. I thought it was one of the most insightful pieces of literature I’d ever read. So I was already familiar with the journey up the river to the ‘horror’. And I was a huge fan of Apocalypse Now; I thought it was a masterwork. I think when I first saw Apocalypse Now, I was in college. I don't think I knew that it was based on Heart of Darkness; it was just this Vietnam film. When I found that out and then read Ellie's notes, I thought, ‘Okay, there's a way to follow both the novel, the film itself, and the behind-the-scenes along that same journey.’ I’d really only seen like half a dozen reels at that point, but it sort of came together in that way, and I think Francis and Ellie liked that approach. They were like, ‘Go. Let's do it.’

(FR): At what point did the audio conversations with Francis come in? Because those tapes were essentially dug out of a shoebox, right?

(FB): Exactly. Yeah, all the footage comes down, and it was 80 hours worth of material. It's just crazy. Outtakes and audio recordings. There was this shoebox that had cassette tapes in it, and I put one into the boombox in the editing room. And there was Francis, [on the tape], freaking out about not getting what he was going to get that day and how the whole thing's going to be a failure. I knew right then that was the throughline for the doc, using those recordings. There were so many of them. I think it was actually two shoeboxes full of these cassettes. They were even dated, so I actually knew when they occurred.

(FR): And to have the artist commenting on the production as it was happening. You can't ask for better source material than that.

(FB): It was an inner monologue, and only Ellie could have gotten it. Imagine Picasso or any artist trying to figure out some work and you could be inside his head. That was the access that Ellie had to Francis.

(FR): When did you start reaching out to the cast and crew and bringing them into the process?

(FB): Pretty much right away. I knew that was going to be a strong element of the story, people reflecting on what had happened. I got the go-ahead from Zoetrope and just started reaching out. Everybody wanted to talk about what happened to them over the course of those three to five years.

(FR): As you started to film the interviews, was it clear to you that there were unprocessed feelings that everyone wanted to exorcise? It seemed cathartic.

(FB): It was therapy. I was suddenly this psychoanalyst going through the trauma. They all had PTSD about it. People just wanted to keep talking. Even when I had everything. I was like, ‘Okay, got it.’ They were like, ‘No, but then there was this other time.’ It was really fascinating. When you make a documentary, it's about discovery. You start to get into the material, then you do interviews, and you learn new things. New avenues open up, and so those were all extremely informative and rich.

(FR): Francis was at a unique spot in his own career at that point.

(FB): The first time I met him — the first interview I did where he was in Napa and he had sort of this purple shirt on — he had just pulled an all-nighter on The Godfather Part III because Paramount told him they wanted a Christmas release, which he did not want to do. He rolled up, and I remember [when] he got out of the car, he looked so pissed. But he came, and he gave an incredible interview.

(FR): When you had all of those interviews combined with all of the archival footage, how did you then go about finding the right cut and figuring out how it all fit together?

(FB): We pretty much followed the outline that I had written after I logged all the footage. I spent a couple of months going through every shot Ellie had and then wrote an outline. We just assembled the film based on the outline. Some things were out of place, and some things didn't really work, but we just got started. I think the first cut was four and a half hours. We just started removing things that didn't fit. It was a process of building the entire thing and then chiselling away, like a sculpture.

(FR): Were there any threads in that initial cut that you would have liked to have included?

(FB): Yeah, you see a little bit of the pre-production and the table reads from the actors, but she also covered the post-production, which was a fascinating journey in and of itself, because there was a ton of drama around finishing the film. Some of which was interpersonal stuff.

One of the editors was a creative contributor to Zoetrope named Dennis Jakob, and he was brilliant. I think Francis actually brought him to the Philippines. I had that in there because I was setting up his involvement in the post-production. At one point, he became so upset with the way the film was being cut that he stole the workprint, went to some motel somewhere, and started cutting up pieces of the workprint, burning them, and sending the ashes back in envelopes to Francis. I think they were pretty much freaking out until they realised he was just using some other film and he wasn't really burning the workprint. I tried to get an interview with him because it was such an amazing story.

We arranged to have the interview, but I think he was having some sort of a crisis. I went to his apartment in San Francisco, and I remember knocking on the door at the appropriate time. I could tell that he was in the apartment because I could hear somebody in there. I was like, “Dennis, Dennis, are you in there? Dennis, I can hear you.” He wouldn't come out. Eventually, he sent me an audio cassette that was probably an hour and a half of him telling his version of the story, which I tried to cut into the film, but it didn't really work. The film was too long, and so we just lost the whole post-production [section.]

(FR): It must have been surreal for you, going into the award circuit and having your peers recognise you so early on in your career.

(FB): Yeah, it was just so thrilling and gratifying. It was wonderful to do, but it was so early in my career. I was like, ‘Oh, I'm going to go to Cannes every year.’ It didn't quite work out that way.

(FR): James Mockoski and the team at American Zoetrope spearheaded the 4K restoration, and it is a different experience. What has this process been like for you to revisit this material again?

(FB): Well, it's so much richer. James went back to the original negative and did the 4K restoration from that. I don't really recall how we coloured the film the first time, but we didn't spend a lot of money on it. I think it was a hurry-up job. Plus, the original film that we came out with was blown up to 35mm, so it looked sort of flat. James is a master film restorer and has done a beautiful restoration that is just so rich and brings you into the Philippines.

(FR): Does the film itself strike you differently today, looking back on it?

(FB): I hadn't seen it in probably four or five years, and I saw it the other night for the first time at the Los Feliz 3 here in LA. Seeing it on the big screen was just a thrill. I'd forgotten how tight the film was. It's very tight. There's no real breathing room in the film. It just goes from one episode to the next episode, and I felt like it really holds up. There are so many films you see that you think, ‘Oh man, that was such a good film,’ and then you see it again and think, ‘Ah, maybe not so good.’ This, I think, really holds up.

(FR): Has anything been illuminated for you about Francis' journey in re-watching the film?

(FB): If you're interested in Francis’ entire life journey, or Zoetrope, I recently read the book The Path to Paradise. It really dives deep into Francis' process and what he intended to do with Zoetrope — how it was an idea factory for film, but also short stories and whatever art that he chose to shine his light on. I saw Megalopolis after reading the book, and I think you have to read that book to understand what he's talking about in that film. Or at least, that's the way it worked for me.

(FR): As a writer/director, were there any experiences for you early on in the cinema that shaped you as an artist?

(FB): I grew up in the 60s with a lot of television. I would say the two bars that I sort of jumped between were The Twilight Zone and Green Acres. One was just terrifying, and the other was so absurd and hilarious. I sort of embraced both of those.

Also, I would have to say The Wizard of Oz was an event. When I was a kid, we didn't have a colour television, but my grandparents did. We would go there, and it was a yearly thing. It was as important to me as Thanksgiving or Christmas, The Wizard of Oz. Just seeing the masterful way that film was created. In every way, it's such an incredible piece of work. I think that had a big influence on me — what the possibilities of cinema were.

Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse is currently available in select cinemas and arrives on home entertainment in 4K UHD from StudioCanal on 28 July. To learn more visit: www.rialtopictures.com

Watch Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse:

FAX BAHR is a writer, director, and producer. Bahr won a directing Emmy for Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. Bahr has screenwriting credits on five feature films and has served as showrunner on eight network television series. His credits include Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa, Malibu’s Most Wanted, In Living Color, MadTV, The Jamie Kennedy Experiment, and Chocolate News. Most recently, he produced the feature documentary Doin’ My Drugs, exploring the AIDS crisis in Zambia. Next, he produced the feature documentary Out From The Ashes, following a Ukrainian family’s harrowing escape from Mariupol after the Russian invasion. He is currently producing the documentary series Our Game, following the indigenous Haudenosaunee Nationals lacrosse team in their quest to attend the ‘28 Olympics as a sovereign nation. Bahr is also directing and producing the feature documentary Unreasonable, The True Story of a Texas Hellcat, now in post-production.