Jaws: The Exhibition │ The Academy Museum

by CHAD KENNERK

Jaws: The Exhibition has surfaced at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Marking the 50th anniversary of Steven Spielberg’s groundbreaking 1975 thriller, the exhibition offers an unprecedented dive into the making and legacy of Jaws.

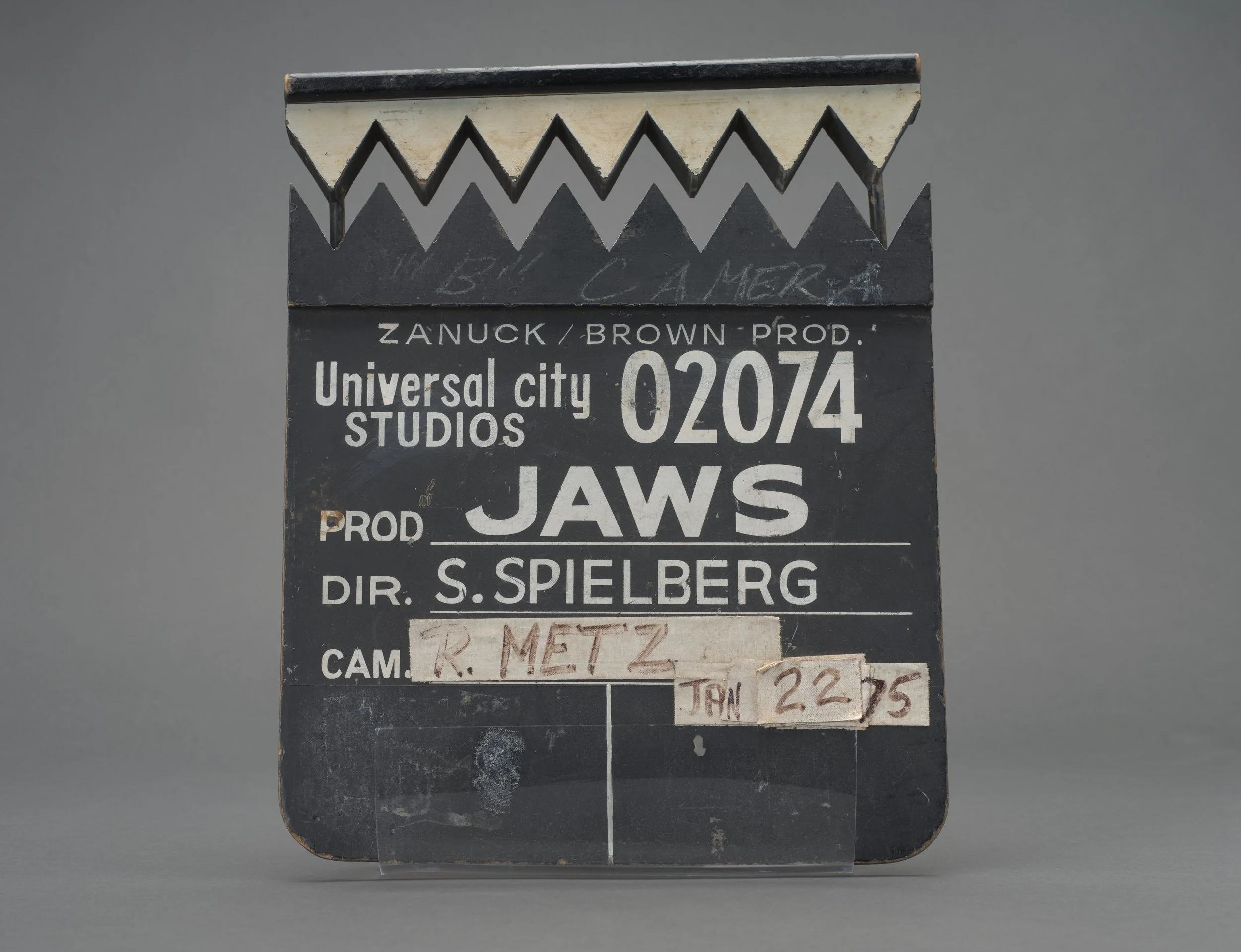

On view through 26 July 2026, Jaws: The Exhibition immerses visitors in a ‘scene by scene’ experience showcasing more than 200 original production objects — many never before seen by the public. Highlights include Spielberg’s own annotated script, Joe Alves’ original shark designs, John Williams’ sheet music, and iconic props like Quint’s fighting chair. Visitors are also invited to explore interactive moments, including the chance to recreate the film’s famous dolly shot and operate a scale model of the mechanical shark. Curated by Senior Exhibitions Curator Jenny He, with contributions from Spielberg, Amblin and the Universal Archives, the exhibition celebrates the ingenuity, cultural impact and lasting legacy of Jaws.

At the exhibition’s press preview, director Steven Spielberg enraptured the David Geffen Theater with stories about the making of his masterpiece. “I never got seasick, and I think that is only because I had the weight of this production on my shoulders; I didn't have time to get sick. But we finally got through this thing, and what got all of us through it was being in the company of each other. That was the key that got us through it. The camaraderie that happens when you're just trying to survive something brought all of us closer together. I've never been closer to a crew or a cast, until many years later, but this was the ultimate example that when you work as a team, you can actually get the ball across the finish line. And we did. I'm very proud of the movie. The film certainly cost me a pound of flesh but gave me a ton of career.”

The filmmaking legend also shared what it meant to have the Academy Museum highlight Jaws in their first large-scale exhibition dedicated to a single film: “The fact that now, 51 years after the production and 50 years after it was released, people have the chance between now and July to come here to the Academy Museum and live for the first time some of the experiences I'm trying to relive for you here this morning. I'm just so proud of the work they've done, what they've put together. This exhibition is just awesome. Every room has the minutiae of how this picture got together and proves that this motion picture industry is really, truly a collaborative art form. [There’s] no place for auteurs. This is an art form that only survives based on getting the best people in all the right positions. It's a collaborative medium, and I am so proud to be part of it.”

In conversation with Academy Museum of Motion Pictures Senior Exhibitions Curator Jenny He.

Film Review (FR): When did you first encounter Jaws?

Jenny He (JH): That's a great question, and I've been thinking about the answer to that. I don't remember a time when I didn't know Jaws. I believe I saw Jaws for the first time on television. I remember distinctively when I saw it on VHS. I was like, ‘Oh, they cut out certain scenes.’ Those scenes really stand out in your mind when you see the unedited version. Jaws has always been a part of my cinema history. It's been indelible in my mind. So to be able to curate an entire exhibition of this film has been such a privilege.

(FR): Bruce has had a home at the Academy Museum for a while now. How did getting a cast from the original production mold initially come about? And did his presence at the Museum help to inspire the exhibit?

(JH): Before the Academy Museum opened to the public, the collections team built the collection from original objects, props and costumes. They went far and wide. Bruce, the shark from Jaws, had always been in the top ten on the wish list. It was really kismet when it was found at a junkyard, at Aadlen Brothers Auto Wrecking in Sun Valley. The story is that after the film opened in 1975, the movie was so popular that Universal wanted to add the shark to the tram tour attraction. So they pulled a fourth shark from the original mold that made the screen-used shark.

That shark hung at Universal Studios for about 15 years, until the early 90s. They wanted a more photogenic shark, because Bruce, the screen-used shark, is like an actual shark: when it's hanging, it’s facing the ground. It wasn't a very photogenic angle. In the early 90s, Universal Studios made a different shark that wasn't related to Bruce from the movie. Bruce was then sent off to the junkyard. Thankfully, Aadlen Brothers saw something in the shark, and along with the cars that they were hauling off of the Universal lot, they took a shark. It was hanging at the junkyard for decades. Jaws fans kept talking about it, and people would peek at it from the highway, because where Aadlen Brothers was, you can kind of see the junkyard from the highway. It became lore, and it became a pilgrimage for people to go and find the shark.

We had an amazing fan reach out to us. His name is Philip Bache, and he told our collections team that Bruce was hanging there. This was about 2016 and we acquired the shark through the generosity of Nathan Adlen and we have restored it. We've collaborated not only with Greg Nicotero, the special effects artist who helped restore the shark, but Greg also spoke to production designer Joe Alves and special effects artist Roy Arbogast to really make the Bruce that we have in our collection true to the Bruce on screen. That has been our largest three-dimensional collection object. So it was really a perfect fit that Jaws would be the first film that we're dedicating our largest exhibition space to. And of course, the 50th anniversary was perfect timing to present this exhibition.

(FR): Diving into this project, what were some of your biggest questions or goals for the exhibition?

(JH): The stories about making Jaws are almost as well-known as the film itself. From the opening gallery to the closing, you are walking through the film sequentially, scene by scene. In parallel to that, we also have behind-the-scenes production stories that are motivated by that scene. To give you an example, there’s the very famous dolly zoom during the attack on Alex Kintner, when Brody realises the shark is at the beach. Steven Spielberg and his director of photography Bill Butler really wanted to bring that dolly zoom into the movie to create the sense of dread. That dolly zoom story is situated where the Alex Kintner attack is in our exhibition. We have an opportunity for visitors to create their own dolly zoom using an augmented reality application as well as an actual dolly setup so visitors can do their own dolly in and zoom out.

(FR): You worked with Universal’s archive, with Steven’s archive at Amblin, and with production designer Joe Alves. Is that where you begin — by finding what's out there and available for exhibition?

(JH): Yes, we hope to talk to as many of the filmmakers as possible. We've been going on a scavenger hunt for both behind-the-scenes stories and also behind-the-scenes objects, and sometimes those two converge. In the case of production designer Joe Alves, we will have on view original concept illustrations that he created to pitch the movie to Universal. This is after producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown had optioned the novel, but before the film was greenlit to go to production. The Universal executives had to find out if this was a viable movie. Nobody had ever created a 25-foot animatronic shark before. Some folks thought, ‘Perhaps we can train a shark to act on screen.’ That might be lore, but that was supposedly discussed. The novel is such a gripping story, and as the story goes, Steven Spielberg just happened upon the galley before the novel was published. It was sitting in Richard Zanuck’s office. He was working with Zanuck and Brown on The Sugarland Express. Steven Spielberg was really gripped by the story.

At that time a director had already been discussed for Jaws, so he didn't think he was going to get the job, but Spielberg pitched his vision to Zanuck and Brown, and eventually got the job. Every element of this movie has Steven's imprint in it. In ‘75, Jaws was Steven Spielberg's second-ever theatrical feature film, but with Sugarland Express and with Duel, which was a television movie, Steven had already made an impression on Hollywood and on audiences. That’s why he was given such leeway to do things that had never been done before. Number one, moving an entire production out of the studio stage to an island on the East Coast and filming on the open ocean, which I believe led to the film’s success.

(FR): You’ve worked with a lot of legends, from Tim Burton to John Waters to Spielberg and more. What is that like for you to have firsthand access and accounts from artists like Steven and Joe Alves?

(JH): As curators, we are the conduit between artists and the audience. It’s always great to be able to speak directly to the artists and to be able to understand their intent in creating their work. As curators, we have a mammoth responsibility to be true to an artist's output, and to me personally, it's all about artist intent. Filmmaking is such a collaborative art form and also an art form that is tied in commerce. The film Jaws is a great example. Not only was it a critical success, but it was also an incredible commercial success.

You can't ever divorce the commerce from the art when it comes to movies, because that is also what drives the industry. Being able to unspool those threads is something that I, as a curator, hope to do. In talking to people like Tim, like John Waters, we also want to ensure that their tone and the tone of their work is expressed truly. It’s the same with Steven’s film Jaws. We look at the nostalgia of the film, we look at the authenticity of the film. What Steven put into Jaws, we want to put that same tone into the exhibition, so being faithful to the tone of their work is really important to us.

(FR): How did you find the overall narrative for the exhibition?

(JH): The stories behind Jaws are as well known as the movie itself, and in that way, Jaws has become mythic. There's so much lore about it. Instead of trying to dissect the lore, I wanted to embrace it. I wanted to look at how passionate fans and the Jaws audiences are. They're not simply fans; they are also people who went on to become ocean scientists. They're people who became filmmakers because they were inspired by Jaws. They themselves add to the lore because they were motivated by the film in their own personal life and in their career.

I also wanted to be faithful to the movie’s lore. One very famous example isn't lore; it’s fact — Steven Spielberg, after the first test screening of Jaws, decided that the discovery of Ben Gardner was not scary enough. At that time, he had no more budget and no authorisation to do pick-up shots or reshoots. He borrowed the prop head of Ben Gardner, and he went to his film editor Verna Fields pool — because at that time he didn't have a pool — and he re-shot that scene. It became one of the most famous jump scares, to this day. Instead of simply telling you that story on a label, we've built out a room, and we built out Verna’s pool to really immerse you into that story. That’s just one example of how we are taking these famous stories and presenting them as an experience for our visitors.

(FR): With over 200 production objects on display, what are some of the highlights or some of your favourite pieces?

(JH): We have 200 original objects on display, and that includes, of course, original props and costume components, but that also includes behind-the-scenes production objects, such as the underwater camera used to film the underwater scenes in Jaws. We also have the Moviola that Verna Fields used to edit Jaws. We have a whole collection of vintage merchandise to really speak about the impact of Jaws and how the merchandising of Jaws worked hand in hand in creating the blockbuster.

(FR): That really changed the way that movies were marketed, because it wasn't only memorabilia; it was TV spots, which hadn't really been used previously. And it was a release with a global impact as well.

(JH): Universal bought 30-second television spots the three nights before the film's release, including that Friday, during prime time. That drove audiences to the theatres that first weekend, and then you had word of mouth. They could have opened in more theatres or fewer, but they chose 409, and they climbed at some point up to 900. After that first weekend, they also used advertisements to sell the first weekend's grosses. All of that worked hand-in-hand to really give you this positive feedback loop where the first weekend’s success led to the second weekend’s success and so on. That also created an international phenomenon as well.

(FR): There is so much lore behind Jaws. What was the biggest revelation or surprise for you in putting the exhibition together?

(JH): The surprise for me is actually finding out how young fans were when they first watched the film. That's the first question I ask whenever I talk to somebody who said that they were inspired by Jaws or says that they're a huge fan of Jaws. I've done anecdotal polling, and it's fallen between ages of five and 12, and that really cements how impactful the film is, because, of course, as a child, you gravitate towards good stories. At its core, Jaws is a great story.

Steven Spielberg crafted this really simple tale of three men versus a shark. It's an adventure story. As kids, we love adventure stories. It’s a deep-seated memory. I think that goes back to your first question: When did I first know about Jaws? And I can't remember a time when I didn't know the film, because it's been such a part of my own history. Even to this day, I’ve asked my friends with kids in that age range, ‘Oh, when are you showing your kid Jaws?’ They’ve told me, ‘Oh, they just turned seven, so they just watched it’, or ‘They were five and a half.’

(FR): Every time we talk about Jaws, we have to bring up shark conservation as well.

(JH): Yes, we will have a robust community and impact conversation related to shark science. Inside the exhibition, we also look at shark sciences within the film's universe and beyond. In that universe, you see Brody looking at books and research on sharks. We have those original props in the exhibition, juxtaposed with the actual shark research that Joe Alves used to design the shark.

Steven Spielberg and Joe Alves really wanted to bring realism to the shark. They exaggerated its size because normal great white male sharks aren't 25 feet long, they exaggerated the size. Other than that, they really went deep into shark research. At the end of the exhibition, when we look at the impact of Jaws, we also surface real shark facts. Going back to your statement about why Jaws became a blockbuster, the teaser ‘Shark Facts’ poster that appeared before the movie opened also had an effect.

(FR): There is an original ‘Shark Facts’ poster in the exhibit as well.

(JH): In ‘75, people really didn't know that much about sharks. So I think that kind of classroom-style poster really brought interest and curiosity for moviegoers before they watched Jaws. Lastly, because Steven chose to film on location, you have the camera on a real beach in the real ocean with a shark that was very much modelled on actual sharks. You could be in the water with Bruce. It wasn't a movie — it was something that felt like it could happen. I think all of that, together with the Shark Facts poster, really generated the interest and curiosity that led to its blockbuster success.

Jaws: The Exhibition is open from 14 September 2025 – 26 July 2026. To learn more and book tickets, visit: www.academymuseum.org

Shop The Academy Museum Store’s curated gift collection celebrating ‘Jaws: The Exhibition’

JENNY HE is a Senior Exhibitions Curator at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. In addition to Jaws: The Exhibition, she has curated exhibitions featuring directors John Waters and Pedro Almodóvar, composer Hildur Gu›nadóttir, animation filmmakers including Tyrus Wong and Pete Docter, special and visual effects artists including Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen, and other subjects for the museum. Previously, she independently curated and toured several exhibitions on director Tim Burton’s work to worldwide institutions, including The World of Tim Burton at the Museum of Image and Sound, São Paulo (2016) and the Mori Arts Center, Tokyo (2014–15). She also co-curated the 2009 retrospective exhibition Tim Burton at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. For MoMA, her film series and gallery exhibitions include retrospectives on Kathryn Bigelow, Lillian Gish, and Pixar Animation Studios. Additionally, she has served as the Programming Director for the South Asian International Film Festival, and on film festival juries including Camerimage, the International Film Festival on the Art of Cinematography.

THE ACADEMY MUSEUM OF MOITION PICTURES is the largest museum in the United States devoted to the arts, sciences, and artists of moviemaking. The museum advances the understanding, celebration, and preservation of cinema through inclusive and accessible exhibitions, screenings, programmes, initiatives, and collections. Designed by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Renzo Piano, the museum's campus contains the restored and revitalised historic Saban Building—formerly known as the May Company building (1939)—and a soaring spherical addition. Together, these buildings contain 50,000 square feet of exhibition spaces, two state-of-the-art theatres, the Shirley Temple Education Studio, and beautiful public spaces that are free and open to the public. These include the Walt Disney Company Piazza and the Sidney Poitier Grand Lobby, which houses the Spielberg Family Gallery, Academy Museum Store, and Fanny’s restaurant and café. The Academy Museum exhibition galleries are open six days a week, from 10am to 6pm, and are closed on Tuesdays.