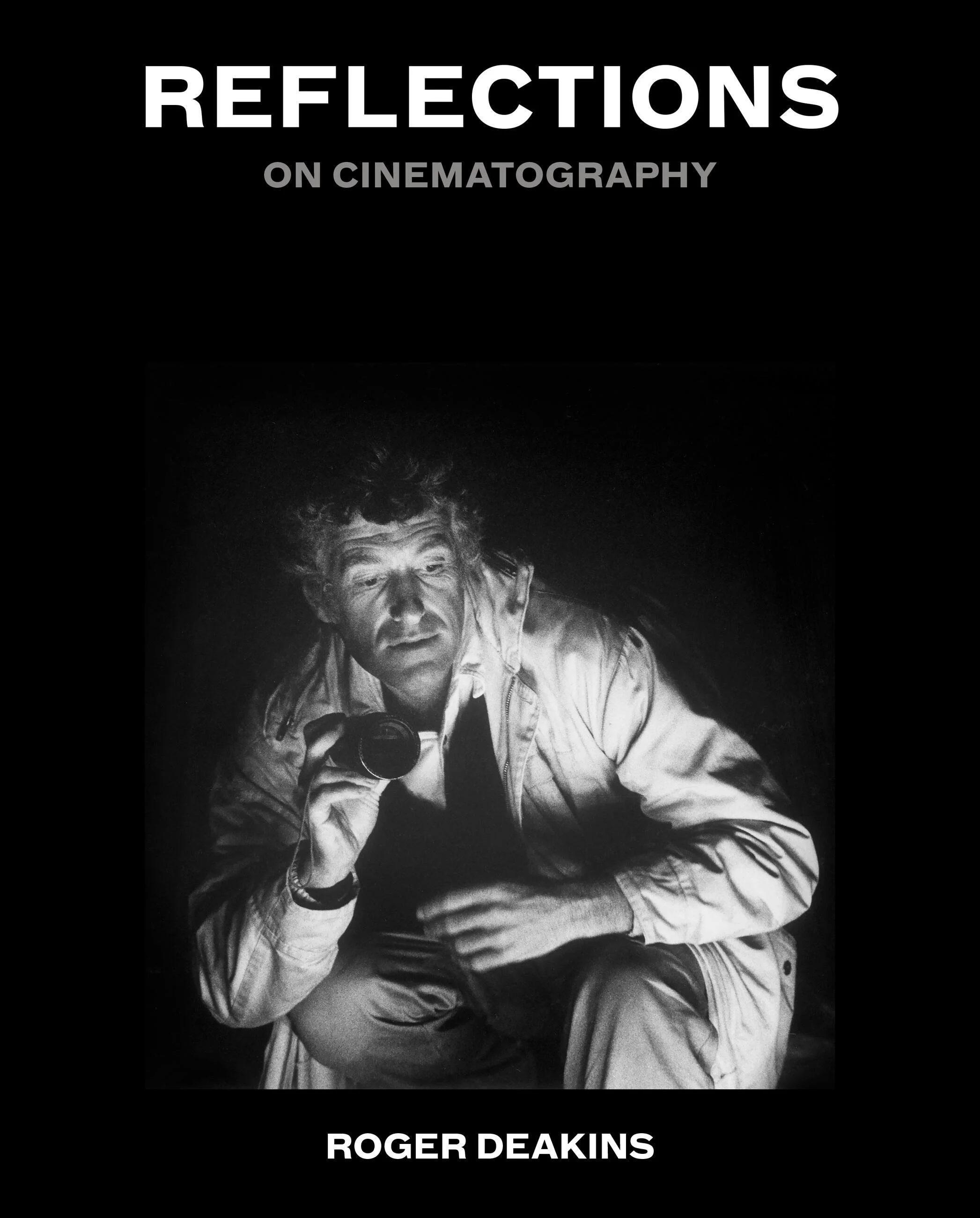

Reflections On Cinematography: Sir Roger Deakins and James Deakins

by CHAD KENNERK

For nearly fifty years, Academy Award-winning cinematographer Sir Roger Deakins has shaped the emotional language of modern cinema one frame at a time. In his new book, Reflections: On Cinematography, Deakins turns the lens inward through a captivating visual memoir that traces an extraordinary career, as well as the philosophy, discipline and curiosity that have guided it.

An autobiography and a masterclass, Reflections charts Deakins’ improbable journey from a restless childhood in Torquay to documentary filmmaking and ultimately to some of the most revered collaborations in contemporary cinema, including his work with the Coen Brothers, Sam Mendes and Denis Villeneuve. Filled with never-before-seen sketches and candid reflections, the book reveals how light, movement and framing meet story, with each project in his prolific filmography becoming a part of the evolving artist behind the camera. Alongside his wife and creative partner James Deakins, Roger Deakins reflects on creating some of the most iconic scenes in cinema history.

In conversation with Roger and James Deakins.

Film Review (FR): Before we chat about this beautiful book, I'd love to talk about one of my favourite podcasts, the Team Deakins podcast. I love it and I learn so much from it. What has that project meant to you, and what have you taken away from those conversations?

James Deakins (JD): I think it's meant a lot to us, because the people that we've talked to, we've enjoyed talking to so much. We do come away from it having a really good experience and a connection with another person that does what we're passionate about. So it's a really great experience.

Roger Deakins (RD): Yeah, talking to a lot of people we've admired for a long time. It's been amazing, actually. We didn't expect it to expand the way it has [laughs.] Now we're just hanging on, keeping it going.

(FR): How do you navigate combining the personal and the professional in your partnership?

(JD): I think it's fairly easy for us only because when we started out, we were working together on a film and did the whole film together, working-wise. We didn't get together until after the film, so our working relationship is our first relationship. If we're in the middle of something personal and work comes up, we flip really easily. We are pretty boring.

(RD): But I don't really separate the two; that's the thing. We're both so into film and the work we do. It's our life. It's just part of our life. I don't know where the separation comes in really, because for the podcast, we watch a lot of movies that people have worked on. We go back in time and watch early movies and all that. So is that work or is that pleasure? I don't really know. We don't separate it.

(FR): When you have a new project, do you approach each project similarly or very differently? Is each one completely unique?

(JD): Yeah, hopefully!

(RD): Of late, I’ve been taking still photographs. We did a book during the pandemic, and I'm trying to organise another one. So each project is different, and we approach it [in] a different way.

(FR): Your work always reinforces the story and immerses audiences in the story. What has the journey been like putting this story together, this book together?

(RD): It was never intended. We were approached by a publisher with an offer we couldn't refuse [laughs.] No, I mean, if somebody says to you, “We'll back doing a book on your life and work.” I mean, what are you going to do? And it's an extension, in a way, of what we've been doing in terms of our outreach, so if it becomes a teaching aid and all the rest, I think that's only beneficial, really. If it can help other people, you know?

(FR): Did you revisit your work in going back and putting this together? Do you like to do that? Do you not like to do that?

(RD): Some things I didn't like revisiting, but most of the things are there in your head anyway.

(JD): You did have to revisit them to figure out which stills you wanted in the book.

(RD): Yes, and the hardest thing was reducing it to a reasonably sized book. The publisher initially wanted something quite a bit smaller and concentrated on half a dozen films that everybody had seen. I wasn't really interested in that; either [you] do it as a broad overview or not. It sort of morphed into what you see; it's a bit of everything.

(FR): It's beautiful to look at too. Did you have input in terms of the layout and what you wanted it to look like?

(JD): Very much so. We were lucky because we asked to be involved in choosing the person that was in charge of the design. We were lucky to find a fantastic person, [Shubhani Sarkar,] who was very collaborative, because obviously we had very strong ideas, and just like a movie is a collaboration, you want ideas from different places to come and make the final product.

(RD): The hardest thing to do was correlate the pictures, the screen grabs, with the text so that you didn't have to put a title on the images. It just flowed within the text. There was a lot of back and forth about the design, scaling things and all the rest. But it was quite a nice process, wasn't it?

(JD): Yeah, and it was a little difficult for her because she wasn't an expert on the lighting technology, so she might think that a frame actually went further back [in the text], but we were actually talking about it here.

(FR): Roger, when you were filming 1984, you talked in the book about finding a new confidence and recognising yourself as a cinematographer for the first time. We all have those moments where we take a step back and are able to look at the bigger picture. Has putting this project together and finishing this book given you a similar moment or perspective?

(RD): I'm definitely given a perspective on my life and career. I mean, that was kind of interesting. Also, that started happening during the pandemic, frankly, the period of reflection. So it was a nice coincidence, not in terms of the pandemic, but that the publisher came in and suggested the book. It made sense.

(FR): And there's so much for filmmakers to take from it in terms of finding simple solutions, doing as much as you can in-camera, not moving the camera unless you have to. What do you hope that young filmmakers will take away from the book?

(RD): Well, I think that. In a way, I wrote it for my teenage self. I'm hoping that somebody like me who had no connection to the film industry and was away from anywhere, could read it and then see that there's a way to fulfil their dreams.

(JD): I think it also shows that you may have the theory of lighting down, but the reality of filmmaking is that the logistics of the set, the budget, and the time schedule — all of that is going to work against you and that you need to fold that in. I think that's really important to teach, because it's much more realistic. It's all very well to have a theory, but you’ve got to figure out how to make it work.

(FR): I've talked to directors about setting the tone for a production, but it's also in the cinematographer's court to establish that. How do you create a sacred space for actors and your collaborators?

(RD): It's a lot of things. It's the choice of your crew. I always operate the camera, so that helps. I like having a small crew rather than an expansive crew. I personally like shooting with a single camera, so that makes it easier to make the set feel intimate. Yeah, I think the cinematographer has got a lot of responsibility in that way. Perhaps as much as the director in terms of the atmosphere on the set, because it's the cinematographer that knows all the crew: the gaffer, the key grip and the riggers. To get that sort of peace on the set and respect for the actors on the set. A lot of it is down to the cinematographer and down to the cinematographer’s choices.

(JD): And the thing is, for a lot of categories, their break comes in between the setups, which is when we have to work to make the setup — to set up the setup. Reminding people constantly that if you have to talk, go off set. It’s a losing battle sometimes [laughs].

(FR): You mention No Country for Old Men in the book and being a witness to a particular scene between Tommy Lee Jones and Barry Corbin. You've both been on sets and witnessed incredible performances. What are a few that stand out for each of you that may have made you forget that you were on a set?

(JD): I think on Shawshank, there's a scene where Morgan [Freeman] has just gotten out of jail, and he's working in a supermarket. He can't take all of the stuff around him, so he asks to go to the bathroom, and he's in a small cubicle. He needs that space around him, and the way he played it, it just made me cry.

(RD): I used to get a tingle down my spine when I was looking through the camera watching an actor. It happened quite a lot on 1984 with Richard Burton. It happened on No Country quite a few times. It's the performance, it’s the dialogue, it’s the whole feel of the scene and the way it draws you in. It's like when you read a novel and you're not aware of sitting there reading words; you're transported into this other world. Sometimes that happens on set. It used to be that I was the first person that was seeing what the audience would see, before they had playback and video assists. The operator was looking through the camera, seeing the image as the audience would see it. Seeing the close-up of Richard Burton as he was saying a particular line or whatever. That was always very moving to me.

(FR): It was really great to hear that memory in the book of Richard Burton sharing such kind words to all of you.

(RD): It was so amazing, because obviously I knew of him from all his movies, but to actually be with him on set was amazing for an early film.

(FR): You talked about honing the book down; were there stories left on the cutting room floor, so to speak?

(JD): Many [laughs].

(RD): Yeah, quite a few, actually. We worked with this writer from Chicago early on, Keith Phipps, and we went through stuff. That's how we focused on what's now in the book. There are a lot of crazy things that happen on film sets. It is a crazy business. That was the funniest thing about going back and thinking about all the movies. You remember all those crazy, crazy moments.

(JD): And we often wondered if the publishers wanted a ‘tell-all book’ and got something completely different.

(RD): Nobody's ever said if it was what they wanted or not, really. But, you know, there it is. They were very supportive because, as I said, originally it was going to be a lot smaller, but we always wanted it to be reasonably inexpensive so that it could reach a wider audience. Even though the book expanded in terms of physical size, they kept to the original price frame.

(FR): I loved hearing about your early adventures, which I wasn't aware of. You went all over the world.

(RD): I wanted to put that in, because that actually was something [where] a publisher said, “We don't need your life growing up in Torquay.” And I said, “Well, I do, because I want to show that you don't have to be born in Hollywood, and you don't have to be connected in any way to actually find a way and be lucky and end up doing what you do, you know.”

(JD): It's a bit of a lie if you don't say that. There are always the early years for everyone where you're just [struggling]. Everything that you do in those early years actually does influence your work later.

(RD): Absolutely, yeah.

(FR): It's an important context. Is there a moment that stands out to each of you that was particularly rewarding, whether it was an individual shot or maybe even the two of you coming together on set?

(RD): Coming together on set, I'd say that. We met in South Dakota on the film Thunderheart. We had both recently moved to Los Angeles, and we actually lived about a quarter of a mile apart from each other. It seemed destined, to me anyway. I don’t know how you feel.

(JD): I also think that there are tons of incredible moments on set, because you're actually seeing the movie and the story unfold that you think you knew so well, but then you're in the locations with the actors, and suddenly there are sides to the story you hadn’t thought of. And you thought you knew it absolutely well, but the actors are bringing so much into it. It's actually quite thrilling all the time. Well, most of the time [laughs.] It's also really interesting afterwards, when you've had a really rough day and you felt like you were just scrounging around getting pieces. You think, ‘How is this going to work?’ And then you see it cut together, because, of course, the editor is normally not there, they have that perspective to be able to pull something together. And that's exciting, to see it and go, ‘Oh, we got away with that.’

(FR): I love that moment in the book where you talk about going to see that double feature of Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves and Terminator 2. And Roger, you talked about the cinemas in Torquay growing up. What have been some either early or very memorable experiences for each of you at the movies?

(RD): I remember going to see Dr. Strangelove with my brother in a cinema in Torquay. I remember we were both walking home and singing Johnny Comes Marching Home very loudly, and we nearly got beaten up by somebody. We lived quite a long way outside of town, so this was late at night, and it was raining. I just remember being so taken with that movie.

(JD): I think I saw a movie one time, loved the movie, and then many years later, it was re-released, and I was in the process of breaking up with my boyfriend. It was about romance, and I went to see the movie and hated it. ‘Why are they whining about this?’ What it taught me is that it really is your mood going into it. You can make a great movie, but someone's going through something, and they're not going to like it.

(RD): Some of my most memorable moments were in this little film society in Torquay just before I was leaving school. I must have been 17, I guess. Seeing films like Alphaville on a little portable screen with a 16 mm projector in what used to be the gas fire showroom in Torquay. Imagine seeing Alphaville for the first time, not really having that much knowledge of film or filmmaking. It was kind of amazing.

Reflections on Cinematography is available now in the US from Grand Central Publishing and arrives in the UK on 12 February. To learn more and read the book, visit hachettebookgroup.com

Listen to the Team Deakins podcast

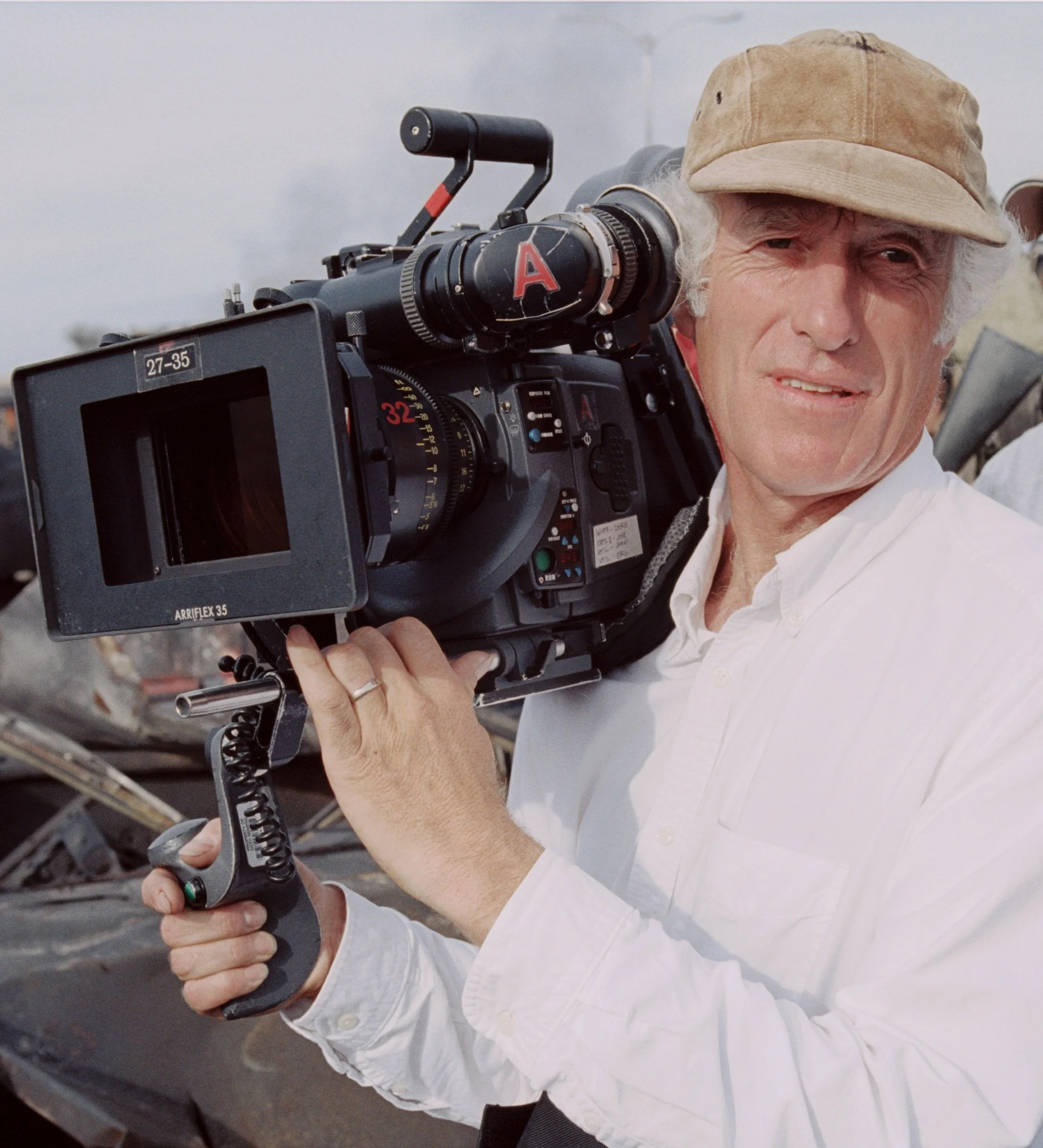

SIR ROGER DEAKINS is widely regarded as the greatest cinematographer of all time. Roger has been nominated for 16 Academy Awards, winning twice for Blade Runner 2049 and 1917. He has also been nominated 11 times for the Bafta award, winning on five occasions. Roger has been awarded Lifetime Achievement Awards from the American Society of Cinematographers, the British Society of Cinematographers, and the National Board of Review. He is also the sole cinematographer to have been honoured with a CBE, in 2013, and a knighthood, in 2021. Roger splits his time between England and California with his wife and long-time collaborator, James. You can follow them @team.deakins.

JAMES ELLIS DEAKINS is the creative work partner of Roger Deakins. She began her film work in New York City as a film lab technician and then as a script supervisor in production. After moving to Los Angeles, she met Roger Deakins on a film set, and their creative collaboration began. She and Roger developed their unique working style, which has continued to evolve over the decades as they enter into new enterprises, including the Team Deakins podcast.