Jaws @ 50: Filmmaker Laurent Bouzereau on the Definitive Inside Story

by CHAD KENNERK

Just when you thought it was safe...

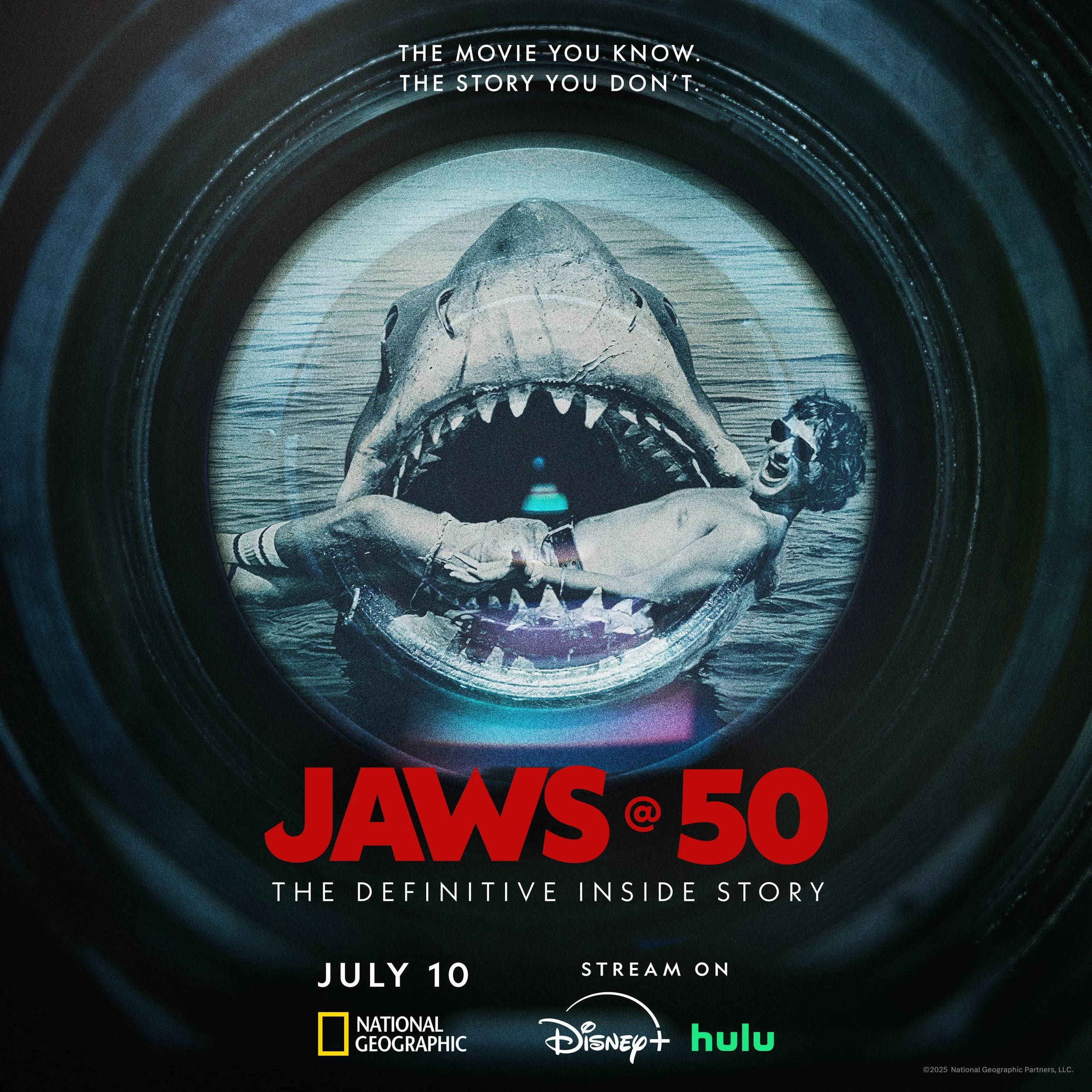

National Geographic’s SHARKFEST is spotlighting the ocean’s most infamous and maligned predator with more than 25 hours of content, including a look into the legacy of Jaws. From National Geographic, Amblin Entertainment and Nedland Media, Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story honours the cinematic landmark but also delves into how Jaws reshaped the movie business and the public perception of sharks. As the icon resurfaces in cinemas and continues to make waves, it’s time to get back in the water and take a closer look at the film that still terrifies and inspires half a century later.

Renowned filmmaker and best-selling author Laurent Bouzereau has spent decades chronicling the untold stories behind cinema’s greatest moments, from documentary films about the life of Faye Dunaway to the legacy of Natalie Wood and the music of John Williams. He is the author behind books on cinema such as Spielberg: The First Ten Years and The De Palma Decade. His connection to Jaws goes back to 1995, when he documented the making of Jaws for its LaserDisc release, an experience that set the stage for his long-time collaboration with Steven Spielberg.

Bouzereau’s documentary Jaws @ 50 offers a true cinematic deep dive into the making of Spielberg’s iconic adventure, providing freshly caught insights from marine advocates and modern filmmakers, never-before-seen treasures from author Peter Benchley and Spielberg's personal archives, as well as in-depth interviews with those who lived the chaos behind the camera. As Jaws @ 50 premieres on National Geographic on 10 July (US), 11 July (UK) and launches of Disney+ (11 July), Bouzereau joins Film Review to discuss the challenges of re-telling the story behind the legend and reflects on the enduring relevance of Jaws.

In conversation with filmmaker Laurent Bouzereau.

Film Review (FR): The 1995 Jaws LaserDisc which included the documentary The Making of Jaws was something of a holy grail for fans to sink their teeth into. Did returning to the waters of Amity feel like a full-circle moment?

Laurent Bouzereau (LB): Yeah, you just aged me by 30 years, but that’s ok [laughs]. I can't believe how fast it's gone. Talk about full circle. When I saw Jaws as a teenager in France, it was the trigger, really, for me to move to America. While the film has inspired a lot of shark research, scientists and movie people, it truly inspired me to want to meet Steven Spielberg. I did move to America, and I did meet Steven, and he did give me an opportunity to do this original, really first look back at Jaws since the film had come out. Now, to be able to do this several years later is beyond a gift.

(FR): Diving back into the history of Jaws — this is a story that you know very well, yet so much has been written about that notorious shoot and the film since your initial documentary. How did you approach organising and encompassing the definitive story?

(LB): That's a really great question, because as I embarked on this project, I was even wondering if I should do it, because there's so many books, there's so many other docs that have been done. Aren't we tired of hearing that the shark wasn't working? [Laughs.] I decided to use that to my advantage, actually, and that's why I have it in the documentary. I asked Steven that question: is there something left to say about Jaws? We go on that journey together and therefore, on a journey with the audience.

I think that there are several things that have happened since that original doc and since Jaws came out. There is, of course, the change in cinema, which is the advent of CGI and how things are done. I think that what the doc is saying is, with the change in technology is this movie still relevant today, and if it is, why is it relevant? Another theme is that I had completely underestimated Steven's trauma with the making of this film. I think there is a real lesson there that applies, not only to filmmakers, but to anyone who is facing a challenge that could change the course of one's career and one's life, as it did with Steven. The message is basically don't give up. I think that makes the story more relatable. My first doc, and I think a lot of the docs that have been made, are very filmmaker-centric. I think this [film] is people-centric.

I also shed a light on the island of Martha's Vineyard, where people are still living off of that movie. It's literally everywhere. It's almost like when you go to Paris and you go to see the Mona Lisa. Well, this is their Mona Lisa, really. I feel that there is that sort of small-town spirit against the canvas of a movie that became a phenomenon. I'm always fascinated by, and I do this in my films, the micro and macro aspects of things. It was really fun to go there; it was the first time for me, actually, and to talk to some of the locals.

Another layer that I really never thought of, but came through my relationship with Peter Benchley and now with Wendy, his wife, was about the shark aspect of this story. I think social media has completely changed the landscape of many things, including shark stories.

There are so many people who reached out to me, who found out I was doing this film and wanted to be part of it, [saying,] “Oh, my god, I love sharks. Sharks are my heartbeat.” It's interesting that the film and the book have evolved into something that's very respectful of nature and the ocean; that's an important message to send. Hence the partnership with National Geographic, which I thought was really inspired because it sends the message of that brand, if I may call it that: stories of great adventure and nature. This is an adventure in moviemaking, but it's as much about climbing a mountain. You may never get there, and you may, by the way, fall and kill yourself on the way.

All those reasons make it a very emotional story to tell, and I have to say, I felt extremely proud of the result. I wasn't sure going into it that I was going to be proud of it [laughs] or that I was going to find a story that felt fresh, new and worthy. Of course, let's not forget the guidance that I got from Steven himself, who was extremely involved and so generous, so enthusiastic, and so fun, and wanted to open his heart about what that experience really means to him.

(FR): You captured all of the elements and strands that have been out there in the Jaws lore and also brought in the conservation aspect to talk about the importance of these creatures and how beautiful they are, as well as how important they are to our ecosystem. As a part of the 50th celebrations on Martha's Vineyard, they premiered Jaws @ 50 on Friday, June 20th — the same date of the island premiere in 1975. What was that moment like for you as a filmmaker, to bring this story back to where it started?

(LB): Well, I'll start with kind of a funny story. I'm from France, right? And I have an accent. When I first came to New York, with the hope of hooking up with Mr Spielberg and his universe, I just kept talking to people about stories of Jaws, wanting to find out anything I could about Jaws. I could not pronounce Martha's Vineyard. I literally had to practise in front of a mirror, and I kept saying ‘Marta Vinegar’ or something. I mean, it didn't sound at all like Martha's Vineyard. I was famous amongst the friends I made for not being able to pronounce the name of the location where the film was made. That could be why I never felt compelled to go there until I could actually pronounce it. When I moved to New York, I remember going to all the locations of my favourite films, including The French Connection and Brian De Palma's films, and being awed by their connection to real life and how much I wanted to be part of the universe of the artifice of film.

Going to Martha's Vineyard, celebrating this anniversary and my film there, it's hugely significant for me personally because you find yourself at a place where an intellectual, creative battle took place. To realise that 50 years later, this is where that creative challenge took place, is incredible. It really is a tribute to filmmaking and to a great artist, that is Steven. Those kinds of movement and benchmarks don't happen that often. I don't think there's been anything that has influenced cinema, nature, filmmakers, scientists, or writers — because it did begin with the great book by Peter Benchley — as much as Jaws has. To be at the centre of where it all took place is only fitting.

(FR): The Making of Jaws was released first, but your collaboration with Steven actually started with The Making of 1941, right? What was that experience like, building that partnership and collaboration?

(LB): It was surreal, right? I remember my very first meeting with him. It was about 1941, but there was also something about Jaws. I said to him, “It's interesting, at the end of Duel, your film about a truck, when the truck goes over the cliff and ‘dies’, there is a weird sound effect. And when the shark at the end of Jaws has exploded and you see the carcass falling to the bottom of the ocean, you have that exact same sound effect. Or am I crazy?” And remember, this was 30 years ago. He said, “No one has ever noticed that before. Absolutely, you're right. It was one of my favourite sound effects at the Universal library; they pulled it out, and I put it in Duel, and then I put it in Jaws as a kind of little inside thing. You're the only one who's ever noticed that.” I think from that moment on, there was this feeling that I understood the language of his cinema. I always approached talking about him as — I don't want to say as a fan — but as an appreciator of his language. He is the Michelangelo of cinema, and there's no one else like him. The humanity that he injects into something like Jaws is pure Steven, and it's why the film endures the kind of success it still has.

I wrote a book on him a couple of years ago called The First Ten Years, and I noticed that if you just look from Duel to E.T., all the films have a home theme. In Duel, there’s the threat of never going home. In Sugarland Express, this couple is trying to get home. In Jaws, they even sing about it on the boat, ‘Show me the way to go home. I'm tired, and I want to go to bed.’ You also have Roy Scheider’s character facing this dual thing, does going home mean New York, or is this his new home? Then, in Close Encounters, the man leaves home. In 1941, the last image is a home sliding down a dune and being destroyed. In Raiders, Indiana Jones is the man who has no home. And then E.T. ‘phone home’. I said that to Steven, and I said, “I know I'm probably thinking all this is a coincidence, but I think humanly, it's not.” And he said, “Laurent, I've never been far away from home.” What he means by that is cinema.

With a great artist, you recognise their touch, their style and their language. I think Jaws definitely belongs to Steven. Sometimes when I look at filmmakers that I've admired, their films are sometimes nothing like anything else they've done, and you don't recognise their voice. With Steven, you always recognise his voice. Not to say that he ever does the same thing twice. He’s just one of those artists that has a resonant, important voice as an artist and as a humanitarian. To me, the lesson of Jaws is really about that sort of timeless nature of those very archetypal characters. We can all recognise ourselves in one of them. Combined together, they represent the most iconic type of movie characters and literature.

(FR): Your incredible body of work talks about so many of the greatest films ever made and the people who made them. Thinking back on the beginning of your career — writing your first book on Brian De Palma, working as a freelance journalist, recording commentaries for Criterion — did you imagine that your passion for cinema would lead you to become the expert on the behind-the-scenes story?

(LB): Well, I'm not an expert, but I appreciate being called that. I knew from a very young age. I don't remember the first movie I ever saw, but I'll tell you something: I remember the first time I was ever in a movie theatre. I never looked at the screen. You know what I looked at? I looked at the beam of light that was coming in from behind. I was just like, ‘How is it possible?’ I lived in a very small town, and my dad arranged for me to go up to the projection booth after the movie. I don't remember what the movie was, but everybody left, and I went up the staircase to see the projectionist.

Now, in my childhood memory, it's 5,000 steps. It was probably like five steps, but it's like that sort of crazy Vertigo shot. And it was like The Wizard of Oz. It was this overheated, grungy place with this guy who explained to me that each time there's a little circle on top in the right-hand corner of the screen, that means he has to change reels. Well, I thought he had given me the key to the greatest mystery ever. Each time I would go to the movies, I’d say, “Look at the little dot there. That means they're going to change.” I found that magical, that such disorganised chaos could create such magic on the screen. It sounds like a cliche, but that's how I felt. So my introduction to cinema was really in being fascinated by the behind the scenes.

When I moved here, I was reminded by an author I knew in New York, “Do you remember you sent me a letter once that said something like, ‘I want to work on Jaws. I want to work on those movies, but I can’t because they've been made already.’ You ended your letter by saying, ‘But one can dream, right?’” And you know what, I got my dream.

(FR): In your life as a storyteller, you have a lot of amazing stories yourself, like being on the set of Moonraker.

(LB): Yeah, my dad was a consultant for the Banque de France, and so was the guy who rented the film studios. My dad said, “Oh, my kid wants to be in movies; can he come to the set of Moonraker?” I had found out that the film was being shot there. And he said, “Sure, send him over.” These were the days where nobody cared, and there I was, on the set [of James Bond], inside of the space station. It was amazing. Later on, I became good friends with Lois [Chiles]; I still talk to her — the Bond woman in the film — and Lewis Gilbert, who directed the film. I wrote a book on Bond, so I got to tell that story to [production designer] Ken Adam and all those great geniuses. I remember going, and I was the first one on set. There was no one else. The lights were down, and I was just looking at this incredible set. And there was the director in the corner, just looking and going, “Oh my god, how am I going to film this thing?” It was just fantastic.

(FR): You also ran into Truffaut quite randomly.

I love Truffaut, because Truffaut meant Hitchcock — and I loved Hitchcock — and it also meant Close Encounters. He had a new movie coming out, The Last Metro. On a Saturday, I was in this movie store that I would go to every weekend. Films were released on Wednesday in France and The Last Metro was coming out, his new film. It's just me and the shop guy, and I'm just saying, Truffaut this, Truffaut that. And he literally walks into the store, and I'm like, “Oh my God.” He bought two books, and I remember my image of him was this youthful guy from Close Encounters with the safari jacket. Well, he was anything but. He was very formal with a tie and a suit on a Saturday. So that kind of shocked me a bit.

I started talking to him, and I said, “I love Close Encounters. I love your movies.” Blah, blah, blah. I started gushing like an idiot, you know? I said, “I can't wait for your new movie.” And he said to me, “I am very scared.” And I was like, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, my past films have not been successful, and I'm just terrified that this is going to be another flop.” I couldn't believe that he was saying this to a complete stranger, a kid. And guess what? That's the movie that literally put him back on the map. It was a gigantic success, and sadly, he passed away only a few years later.

(FR): Does it feel, looking back on your career, that it was a dream come true?

(LB): I don't take any of it for granted, you know? I'm extremely grateful for the opportunities that Steven has given me, not only with this, but [also with] my film on John Williams, my film on Faye Dunaway, [my film] on Natalie Wood, [and the TV series] Five Came Back. My whole career I literally owe to Steven, and I've told him that many times. And yet, I don't take any of it for granted, meaning that I don't feel like I'm owed anything or that I should be the guy doing the documentary on Jaws. I work really, really hard each time I propose a project to explain what my vision may be and why I'm the right person to do this. None of it has fallen into my lap easily, and it continues to be a challenge. But there wouldn't be any drama if it wasn't challenging. I embrace the challenge, and I embrace those movies coming out of it.

I've had an incredible year and a half with Faye; I was in Cannes with her and with John at Mann's Chinese Theatre. Then I did this little film on Hitchcock for StudioCanal, and then my book on Brian [De Palma] and my book on Steven. I am just really blessed and very grateful. I still have a lot of ambition. I want to direct scripted movies. I've been developing some stuff, and I've had a couple of false starts, but I’m hoping that at some point it will happen. I feel like I've evolved, you know? And that's the nice thing about looking back at what I did 30 years ago and what I just did: is that I feel like I've evolved.

At the time, I wanted it to be the ultimate encyclopaedia on Jaws, the ultimate dictionary. There's something very impersonal about that, and I think this new film is much more about the human angle. I approached it with emotions and with great empathy for everyone involved, and really tried to find a compelling story for young people who may not really care that the shark didn't work, or would say, “Hey, I can fix that today. I would just do it in CGI. So what's the big deal?” There is no point of reference for them, but I think that the idea of being someone so young, like he was, and so successful up until that moment and then not knowing the outcome of this gigantic creative challenge that he's thrown in is an inspiration for anyone who tries to do anything. That's most people, and I think young people will hopefully find inspiration in the Jaws Steven Spielberg story and may want to apply it — even if they're working on Wall Street.

Learn more about Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story and SHARKFEST.

Watch Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story:

LAURENT BOUZEREAU is an award-winning filmmaker and best-selling author. His films, co-produced with his partner Markus Keith through their production company Nedland Films, include the feature documentary Jaws @ 50 for NatGeo/Amblin, Faye about legendary actress Faye Dunaway for HBO/Amblin, the award-winning documentary Music by John Williams, produced by Steven Spielberg and Amblin/Imagine, the Disney+/Lucasfilm documentary Timeless Heroes on Harrison Ford, the HBO feature documentary Mama’s Boy, based on the best-selling memoir by Dustin Lance Black, and Natalie Wood: What Remains Behind, as well as the acclaimed Netflix series Five Came Back (with an Emmy winning narration by Meryl Streep), executive produced by Steven Spielberg and Amblin. Bouzereau is the author of several books on cinema, including Spielberg: The First Ten Years (2023) and The De Palma Decade (2024).